Oculars Wide Open: The Power of Live-sharing Our Microscopical Views

By: Jenny Jacox, SFMS Secretary, Co-Editor of MicroNews

Photo credit: Caren Quay

In the little town of Muir Beach, California, there is a mailman who, despite servicing a town with the word “beach” in its name, has never been down to a tidepool. I met this mailman while I was out on a run – which is when I meet so many people that I never forget. I was jogging toward ‘the bench’ – a bench splintered and rotting but humbly presiding over a 180-degree view of Bolinas Bay, Duxbury Reef, and the Pacific Ocean – when I passed by and waved hello to a tired but smiling middle-aged man who, as it turned out, was covering a postal shift for the local mailman. A few minutes later he pulled up alongside me. “Is there an ocean view this way?” Well, yes. Only the view I grew up gazing at for hours. The one that in large part inspired me to become an oceanographer.

We both ended up there at the bench – not sitting, but standing 6-feet apart and talking through masks necessitated by the COVID pandemic – and it was then that he wondered about the reef he could now see below us. He had never been down to see anything like it up-close. He couldn’t imagine doing that.

Lately I’ve been thinking about that mailman, but also about the high school kids from East Oakland, whom I mentored through the ¡Youth & Oceans! (¡YO!) program, at UC Santa Cruz. The program transported minority, inner-city high school students to the ocean’s edge, where we engaged them for a week in marine observation and experimentation. While cleaning up one day mid-week, I discovered that my student team had placed protective Post-It notes all around the experiment they had spent the day designing. I still have those notes (“DO NOT TOUCH!” “Experiment in progress!”, “GO AWAY!”). “Students participating in such programmes [as ¡YO!] develop a deeper understanding of the nature and practices of science than they do in school settings, gain access to valuable information about educational trajectories and the college experience, and may even reduce the effects of stereotype threat by developing a sense of agency in science. In addition to developing STEM interests and skills, students also developed feelings of shared responsibility and stewardship for the ocean and ocean life, both within themselves and their family.” (Fauville et. al., 2008). Indeed!

Sadly, the students mentored through ¡YO! were only a lucky few. Our public schools are ill-funded, and programs like ¡YO! are rare. Let us remember the more typical story of students attending schools that cannot afford science teachers, let alone school bus trips to the ocean. To say nothing of microscopes. There is a very current, very real, very emergent isolation from science on both the macro and micro scales.

But now, here we are, learning in the age of COVID and all of us more learned in what it is to be isolated. Isolated from each other, and from our places of learning. Our classrooms, our laboratories. The pandemic exposed brutal inequities; there were also niches in where it served to equalize. Suddenly, it was all of us, not just inner-city youth, that found ourselves cut-off from access to wet labs and microscopes.

In our household, distance learning began in April 2020 and it looked like it does in many public school districts: my daughter sits at her laptop and does four hours of ‘synchronous learning’ (basically a ZOOM call with her second grade class, the shift from subject to subject punctuated by ‘yoga flow’ or ‘dance break’ routines) and then two more hours of work on her own. Having my daughter’s ‘classroom’ in the home gave me an intimate view of modern elementary public school curriculum, which allots ‘science’ 15 minutes, twice a week – usually packaged as a video. As a mom and scientist, this quickly became more than I could bear. It was akin to watching children try to learn the game of baseball – how to hit a ball, catch a ball, steal a base – by watching reruns of games past.

So, I called my former PhD advisor and told him I needed to get my two daughters out doing the phytoplankton monitoring I used to do in graduate school. I needed my daughters to feel the ocean and to record and know its temperature for themselves. I wanted to show them the beautiful microscopic diatoms and dinoflagellates that live year-round in our coastal waters.

We got outfitted, we went sampling, and one day soon enough my daughter’s second grade class was spending their 15 minutes of science listening to my daughter describe our ‘science’ - sample collection, water temperature, water color, phytoplankton. Afterwards, one student in class said she wanted to “someday be like our family”. Another, wiggling and hardly able to keep still, said, while looking from side to side, that he didn’t know what he was curious about yet, but was excited to find out. My first thought was: And they haven’t even seen the sample under a microscope. Yet.

A few weeks after that 15 minutes, fresh home from an early morning sampling, my daughter sat in her virtual daily class meeting. When asked if anyone had something to share her hand went up. Yes, yes she did have something to share, and when called upon she asked if she could share her screen with the class. The screen she shared was a browser window which held a live view of the sample that was sitting under our microscope. For weeks I had been working towards bringing the plankton sample to the students virtually, sending planning and scheduling emails back-and-forth with the teacher. My daughter taught me a powerful lesson that day, when she simply flipped the switch and live-shared microscopic marine plankton with her classmates for 45 minutes. It was 45 minutes of gasps, oohs, comments, and questions - i.e., science.

Collecting a phytoplankton net tow at Monterey Municipal Wharf #2 in Monterey, California. A phytoplankton net tow is a sample of concentrated seawater, collected by towing a net with an attached cod end through a volume of seawater.

Photo credit: Mike Jacox

Taking the temperature of the ocean. Here, a probe thermometer records the temperature of a marine phytoplankton net tow. A phytoplankton net tow is a sample of concentrated seawater, collected by towing a net with an attached cod end (here, the grey cylinder) through a volume of seawater.

Photo credit: Mike Jacox

Author’s daughter, live-sharing a phytoplankton net tow with her second grade class.

Photo credit: Jenny Jacox

That email to my advisor not only expanded my daughters’ education, and the horizons of her classmates, but also connected me with a network that had begun pre-COVID and, under the stress of the pandemic, had grown in previously unimaginable ways. At the recommendation of my advisor, and sparked by a chance encounter while sampling at a local pier, I joined a no-cost, no-credit course on plankton sampling and identification, offered through Cabrillo Community College, in Santa Cruz, California. Suddenly, every Friday, I was joining and advising thirty students and three instructors who meet weekly to peruse and discuss plankton samples collected same-day from four sites along the Santa Cruz coastline. That’s 66 eyeballs focusing, weekly, on live samples from different sites, under a microscope, together. When the course began, the lead instructor was in Hawaii - and she simply steered the ship from there.

Half of the enrolled students are 20-somethings looking for a taste of ‘real’ science; the other half defy a single definition - besides, perhaps, marine plankton-philes. They are wildlife photographers, data analysts, interpreters, naturalists, retirees, scientists, etc., of varied ages. Coming together as they do, they form not only a class but a community.

Like me, there was one other ‘student’ in the course who was joining - and sampling plankton - from a location beyond the Santa Cruz area. Janai Southworth, a fellow SFMS Member, lives in San Francisco and collects samples from the Torpedo Wharf near Chrissy Field. Soon after meeting Janai in class, I learned that she live-streams her microscopical views into classrooms as a volunteer educator for The Greater of Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, since she no longer can sit in the interpretive visitors’ center at Chrissy Field and allow school groups and tourists to peer, in-person, into the microscope oculars.

Janai also live-streams plankton to the public on Monday and Thursday nights through a live-streaming platform called Twitch. To give you some perspective, on 18 Feb 2021, Janai had over 200 people watching her stream. That’s 200 people looking at the same live sample, under a microscope, simultaneously, from around the world. And it’s a diverse audience: Janai is now exchanging views - and samples - with expert diatomists and microscopists. This is not one-way education.

Janai bought herself a microscope for her 50th birthday, the pandemic having isolated her from her teaching microscopes at Chrissy Field. She learned about Twitch.tv, the online live-streaming service, and began streaming on a bit of a lark, never imagining she would end up with hundreds of people watching her explore microscopic life in seawater. The live-stream is free, and Janai forwards any money that comes from donations or subscriptions (e.g. for ad-free viewing of past streams) to the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. Janai’s love of plankton is pure: she often describes her seat at her microscope, when there’s a fresh concentrated seawater sample in view, as her “happy place”, and she uses her background in fine arts and her made-for-radio voice to share that happy place with a larger, and rapidly growing, audience. It’s a “happy place” that anyone with a laptop and internet connection can step into.

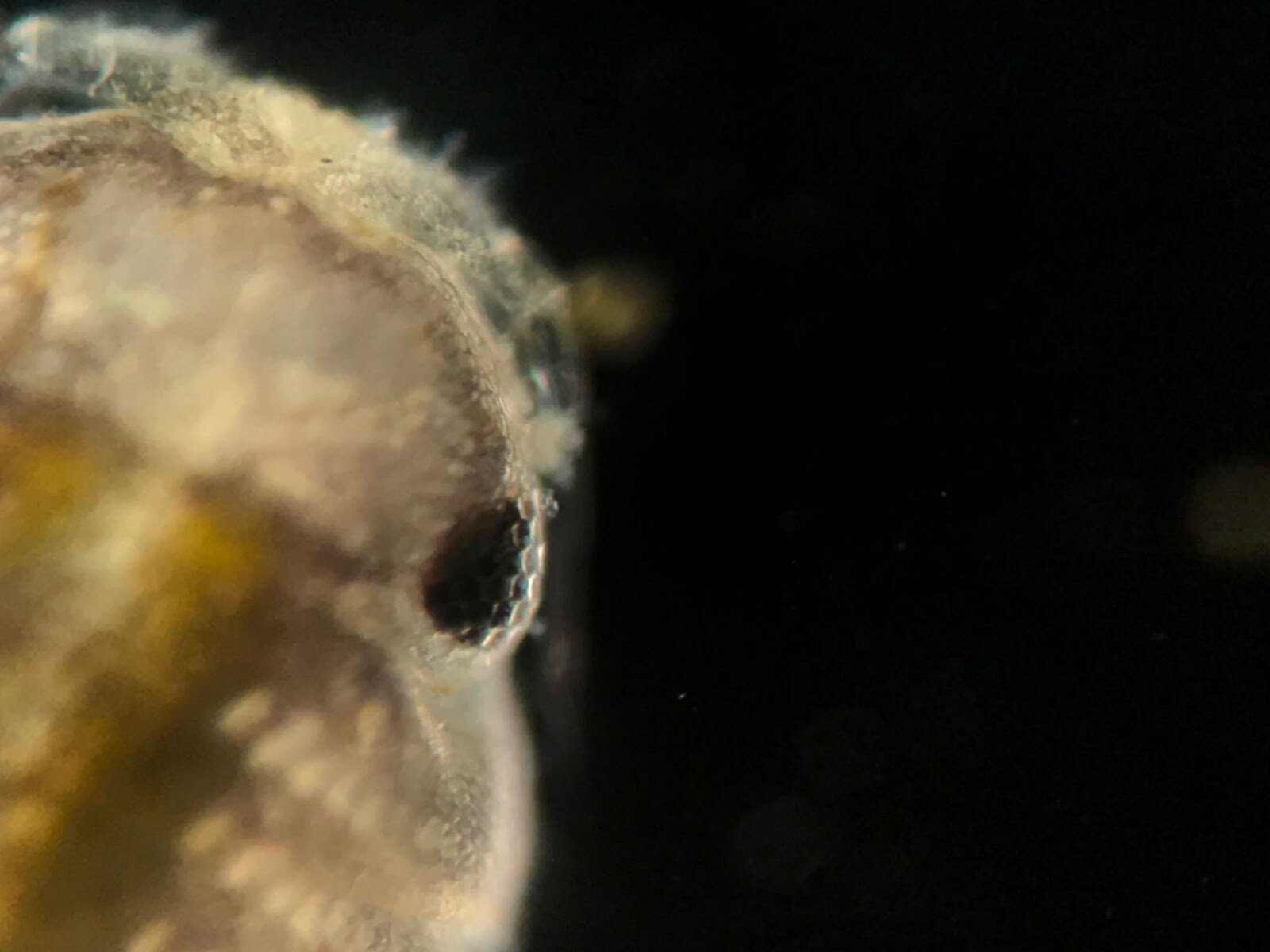

Two Cnidarians from San Francisco Bay. Photo credit: Janai Southworth

* * *

In a This American Life episode, Ira Glass’ co-worker, Bim Adewunmi, says: “… an important part of delight is that it's an invitation. By loving something, we allow other people an opportunity to love it too-- sharing, tapping someone on the shoulder to say, hey, look! So, often I feel like I've had the experience of walking through the world and not seeing anything. And then someone's like, did you see how that -- ? You don't see it until you see it. And then when you see it, you're like, whoa!” (Episode 692: The Show of Delights). It was Janai who introduced me to SFMS, and within a few days of sitting in on a brainstorming meeting with Ariel Waldman, Taylor Bell, Myron Chan, Hank Fabian, Jun Axup, Natalie Downe, Anna McGaraghan, Simon Wilison, Janai Southworth, and Henry Schott, I was sending in my membership dues. We were a motley crew from a diversity of fields but, as I suspect is true for the Society at large, united by having peered into a microscope and saying “whoa!”

Our brainstorm was about the direction of the SFMS, and what activities will shape that direction. I found myself in the midst of this brainstorm at a time when my mind was swimming with what I recognized as a new scientific tool (E.g. We can reduce some of the error introduced into phytoplankton monitoring by drift, bias, and miseducation through virtual cross-checks and roundtables via live-streams from physically distant sampling sites.) and, increasingly, as a way to provide access to those without regular access to science or to the ocean, let alone the unseen microscopic life it contains. So many are like the mailman who crisscrosses Muir Beach but has never been on the rocks that jut from the sand, walking through the world and not getting a closer look. It is my hope that SFMS will do service by tapping those around us on the shoulder to say “hey, look!” With today’s ability to beam live microscopical images to anyone with an internet connection and a laptop, we have a new powerful way to say “hey, look!” to those who have never been invited to do so before. Everyone, wherever they are, at once. No need to wait for a turn at the oculars.

This is a service that is exquisitely needed at precisely this moment, born of necessity out of the isolation that was required of us all, equally, by a pandemic. We hear so much about the very real digital divide that the pandemic has exposed. Schoolkids who do not have internet access or laptops largely do not have access to education. But the pandemic has also shown a way we can now – and into the future – bridge the divide that exists between so many schoolchildren and their natural world; between so many people and science.

I invite you to consider how many perspectives a single, traditional microscope can change in its lifetime. Now, imagine that same microscope outfitted with a camera that is connected to the internet. Janai’s activities serve as a model for the exponential math to be done here. Through the portal that is a single internet-enabled laptop in a full classroom we can open a real-time microscopical window into coastal waters. Or ask students - or anyone - to simply look around and pick something in their world that they have never ‘seen’ but maybe, maybe, with this prompt they find themselves curious about – and then show them how it looks on the microscopic scale.

Whoa.

Isopod from San Francisco Bay. Photo credit: Janai Southworth

Watch Janai Southworth (a.k.a. Pacific Plankton) live-stream her microscopical view of her plankton sample every Monday and Thursday from 9-11pm.

View additional videos from Janai’s Twitch.tv stream.

Read weekly phytoplankton reports from Monterey Municipal Wharf #2 and Santa Cruz Municipal Wharf.

Listen to The Show of Delights (This American Life).

Want more information or have questions? Connect with Jenny via email or direct message in Slack.

Do you have a Perspective to share? Please do, via email.