Truth and truffles

By Maria Pinto

This article was generously contributed by friend-of-SFMS and writer Maria Pinto. Maria recently spent time with SFMS Treasurer Jasmine Richardson on Jasmine’s truffle farm, where she discovered much more than could ever meet the eye (even with a microscope).

The author, Maria Pinto (right), with SFMS Treasurer Jasmine Richardson on Jasmine’s truffle plot. Maria is holding a Berkeley’s polypore (Bondarzewia berkeley) that she found a few miles away from Jasmine’s farm.

Before I looked through the eyepiece of Jasmine Richardson’s microscope at her nascent truffle farm in Virginia back in September of 2021, the last time I’d touched a similar tool was in high school chemistry class, about two decades before. Those early aughts days in Mr. Cinquino’s post-lunch class failed to ignite in me an interest in the microscopic world (even though my teacher had the kind of sarcastic, deadpan delivery that could convince millennial teens they were in collusion with their educators, that grasping a subject or skill was almost as cool as failing to grasp it). But there was something about the world of expensive machines and tiny specimens and tweezers and glass slides and solutions and mounts and objectives that felt too finicky for the likes of me. Getting it all right seemed very complicated—much less getting it all so right that I saw exactly what I was “meant” to see, and could come to conclusions based on that. I’m similarly unmotivated to take on baking projects that go wrong if your measurements are off by three grains of flour.

Since September, however, I’ve come to realize that it wasn’t the tool or its accessories or even my lack of patience for precision projects that were to blame for my failure to take to microscopy as a young’un. It was just that in high school, I had little interest in the things we were using the microscope to see more clearly, like hair of different colors or onion skin cells. This is not to say those things aren’t interesting way up close to somebody… but those high school encounters lacked, for me, the drama of expectancy.

The author and Jasmine struggle to find lateral roots of a downy oak tree (Quercus pubescens). Oaks establish tap roots before they focus their energy on growing lateral roots that form ectomycorrhizas. It usually takes 3-4 years before lateral roots are easily sampled. By that time, the lateral roots covered in black truffle mycorrhizas will start to form "brûlés" or "burnt" areas when the fungus produces VOCs that act as a natural herbicide around the truffle trees.

It was Jasmine, a professional microscopist, fellow mushroom nerd, and budding farmer with a vested interest in the fungal world beyond reach of the naked eye, who could entice me down to the microscale. On her farm, I was learning to tell the difference between a root that had evidence of black Périgord truffle mycorrhization and a root that did not. When she turned the light on at that root tip, she gave me the gift of the mushroom hunt in miniature—a search actually meaningful to me. We were looking for a sort of “hairy” “glove” around the “finger” of a Quercus ilex root we’d excavated. That isn’t what we saw (much to our chagrin), and those roots even showed evidence they’d been colonized with something undesirable. But that disappointment did not quell the thrill I felt at seeing fungal material so magnified for the first time! I was instantly enamored.

The author viewing verified Tuber melanosporum mycorrhizas that had been freezer-preserved and defrosted for comparison of morphology to the mycorrhizas found in the field.

Since then, I’ve studied micrographs of the spores of different mushroom species. Tuber melanosporum has some beautiful ornamentation—with its structures that look like eyelashes—and I look forward to examining those spores in the flesh with my own microscope soon. That’s right: while I’ll likely always be a little more at home in the woods than at a microscope, I will be acquiring one this year (with Jasmine’s guidance, of course), so I can take my study of mushrooms to the next level.

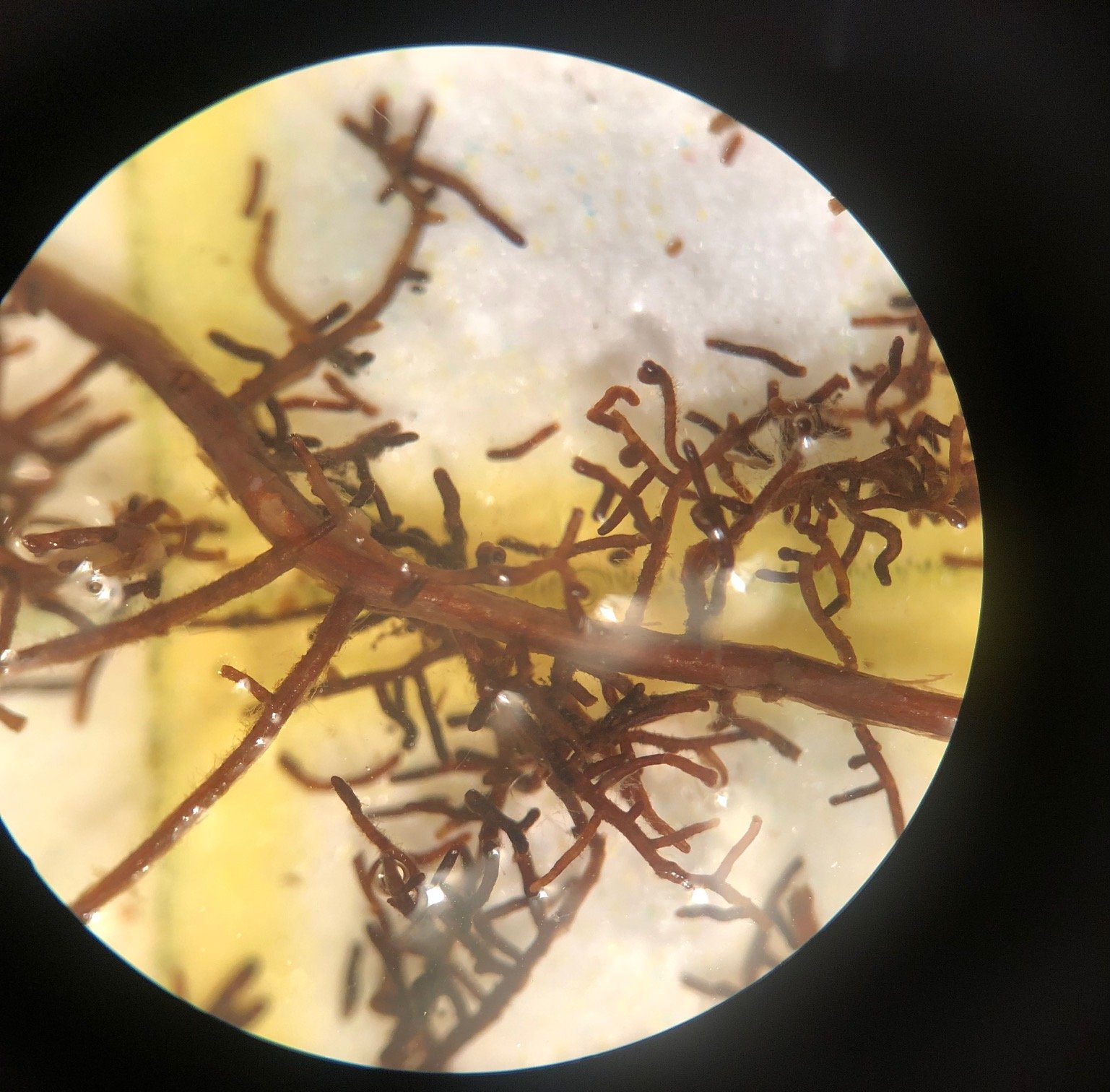

Freshly analyzed bur oak seedlings (Quercus macrocarpa) heavily colonized by Tuber melanosporum.

When I asked Jasmine what had originally drawn her to microscopy, her answer was part practical (of course it would benefit her to be certified in such a niche field) and part poetry: that, at heart, she is a problem-solving truth-seeker. I’m happy to say that she’s now planted the seed of a seeker of microscopic truth in me.